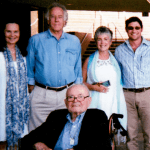

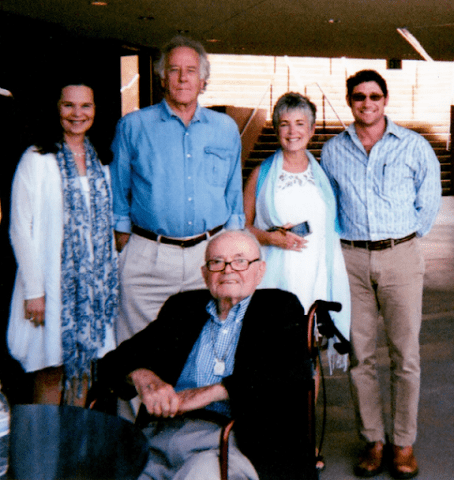

Kathy's mikveh celebration with (from right to left): Rabbi Shai Cherry; the author; the author’s husband, John Ratajkowski; and dear friend of author, Kay Allgire. Forefront: the author’s father, Ely Balgley. Photograph by close friend, Sherry Rosenthal. Taken with permission from https://www.kathleenbalgley.com/

By Tasha Ackerman

On July 28, 2025, author and educator Kathleen Balgley stood among the crowd gathered in Brest, Belarus, for the unveiling of Memory Embrace. The new monument, built from fragments of broken Jewish matzevot (headstones), rises on the site of Brest’s Jewish cemetery, which was once the resting place of more than 35,000 Jews before it was destroyed during the Nazi occupation.

For Kathleen, being there was more than symbolic. It marked the culmination of decades of searching, writing, and returning. When she and I later met over Zoom—her in a hotel lobby in Ireland, me in Tel Aviv—I felt how deeply our stories intertwined. Both of us are drawn to this work of restoration: preserving what was nearly erased, reclaiming identity, and passing memory forward to future generations, or as The Together Plan’s mission puts it, preserving the past for a better tomorrow.

When I first spoke with Kathleen a few months earlier in May, I was struck by how many parallels our lives seemed to hold. She is the daughter of a Catholic mother and a Jewish father; so am I. Her father had shed his Jewish identity, while my own father’s Judaism was muted by my Catholic upbringing. We both have been to the mikveh for a conversion, though both think of it more as a return; a reclaiming of something that was always there. Something deeper pulled us back toward Judaism, not out of obligation, but out of something that felt fated.

Kathleen calls it bashert, often translated as destiny or serendipity. She uses this term to describe this deep sense of familiarity. She first felt it as a child visiting her Jewish grandparents’ house in Brooklyn, writing that it was “an unknown place that I somehow knew.” That uncanny sensation, she later realised, was the beginning of a journey that would take her across borders and back through time. In Poland, Belarus, and Israel, she continued to encounter this same pull: places that felt like returns, and people who felt like bashert.

Kathleen’s journey began decades ago, and perhaps it was all inspired by that feeling of bashert she first experienced at her grandparents’ home. Kathleen’s father, Ely Balgley, was born in Poland and emigrated to the United States as a child. From a young age, he had decided to keep much of his heritage secret as he acclimated to life in America. As Kathleen grew up and discovered her roots, she became drawn to them, confused by the ambivalence her father felt toward his Jewish heritage. In 1987-1989, Kathleen was awarded a Fulbright scholarship to teach American literature to university students in communist Poland. Beyond the scope of her professional responsibilities, she investigated the unspoken history of Polish antisemitism as well as the fate of her own family.

In 2012, Kathleen travelled to Belarus to visit Brest, where her father was from. In the city archives, with the help of her guide Nina, she uncovered stacks of ghetto passport photos, bearing her family name. She noticed the variety of spellings, but what struck her most were the faces: relatives spanning from the ages of two to ninety-five, nearly all of whom had been annihilated. She describes laying hands on the heavy paper files, her guide whispering, “I have chills,” as they realised the magnitude of what they had found. Kathleen recalls being overwhelmed by finding the names and faces long buried. Even the mundane documents, such as an application to demolish a fence, marked the contrast between everyday life and what was unfolding around them. Ordinary lives had been cut short in the most brutal way. To this day, the shock of those records haunts her.

Brest, once referred to as Brisk by the Jews, had been a centre of Jewish life for centuries. Before World War II, more than 20,000 Jews lived there, making up nearly half the city’s population. When the Nazis occupied Brest in 1941, they murdered nearly the entire community, many in mass shootings at Bronna Góra forest. After the war, under Soviet rule, the memory of Jewish Brest was further erased.

The city’s main Jewish cemetery, founded in 1835 and once home to more than 35,000 graves, had been destroyed by the Nazis. Then, under the Soviets, most of the cemetery territory was repurposed as a sports stadium. Only decades later did fragments of the past begin to resurface, leading to the recovery of more than 1,200 headstones and the eventual creation of the new memorial. In 2014, The Together Plan learned about the salvaged, remnant gravestones that were being found around the city of Brest and helped to raise funds to protect and sort those that had been discovered to date. In 2021, the charity signed an official agreement with the Brest Authorities to work exclusively with the gravestones. The Together Plan then found the support that enabled them to photograph and catalogue every piece. They ran a significant campaign to raise the money needed to build the memorial, which was opened on July 28th.

In the past years, Kathleen revisited these experiences while writing her book, Letters to My Father: Excavating a Jewish Identity in Poland and Belarus, which was published in 2022. Kathleen describes her search for family history, her time as a Fulbright scholar in Communist Poland, and her later return to Belarus, where she uncovered archival traces of relatives annihilated in the Holocaust. The memoir weaves together family stories and anecdotes from her years abroad with social, historical, and political reflections that are rooted in compassion and deep consideration. Kathleen empathetically reflects on the world around her as she is trying to understand her identity and relationship to these spaces.

Read more about Kathleen’s journey in her memoir: Letters to My Father.

- Kathy’s mikveh celebration with (from right to left): Rabbi Shai Cherry; the author; the author’s husband, John Ratajkowski; and dear friend of author, Kay Allgire. Forefront: the author’s father, Ely Balgley. Photograph by close friend, Sherry Rosenthal. Taken with permission from https://www.kathleenbalgley.com/

- Kathleen Balgley, taken with permission from https://www.kathleenbalgley.com/

- Letters to My Father by Kathleen Balgley. Image taken with permission from https://www.kathleenbalgley.com/

In July 2025, Kathleen returned to Belarus for the opening of the Memory Embrace. Thirteen years after their archival discoveries, her guide Nina was waiting at the hotel to greet her. The journey was not easy: border restrictions and long interrogations- at one checkpoint, Kathleen’s American passport nearly prevented her from leaving Belarus. Yet she persisted, rather than letting these challenges spoil her trip, they could serve as a reminder of how important it was for her to be there.

The memorial itself, she said, was breath taking. The salvaged, rescued gravestones, set upright on a newly formed central mound of the memorial that sits on the territory of the old cemetery, reminded her of Stonehenge. Around the circle’s perimeter, fragments too small to stand had been embedded in a low wall, forming a mosaic which transformed the broken and shattered pieces of matzevot into a single collective work. Visitors placed small white stones on the memorial, echoing the Jewish ritual of leaving pebbles on graves.

And then there was the weather. That morning, there had been torrential rains. Yet as the opening ceremony began, the skies cleared and sunlight broke over the stones. When the ceremony ended, the rains returned. Kathleen and Debra, the Together Plan CEO, looked at each other in amazement. Bashert, they said. At the reception that followed, Kathleen gave a personal testament about her connection to Brest, emphasising the importance of such memorials.

After leaving Belarus, Kathleen continued her travels in Ireland and Germany, further connecting with relatives and friends. Her journey has deepened her connection to heritage not only through the stories she has uncovered, but also through the relationships that continue to grow. Sharing a Friday night Shabbat meal is as much a part of this journey as opening a box in the archives. And as she continues to share her story through Letters to My Father, she extends those connections outward, inspiring others to explore and take pride in their own heritage.

For Kathleen and for so many of us, these acts of memory are not abstract. They are visceral, grounding, and necessary. Standing at a memorial in Belarus or reading a Jewish heritage memoir is not just about history; it is about belonging. It is about recognising ourselves in stories and realising we are part of a larger circle. These memorials matter because they give us something to touch, to learn from, to connect through. They restore dignity to the dead and offer continuity to the living. They remind us that even shattered stones can be gathered, repaired, and placed back into the embrace of memory.

When I asked Kathleen what it all meant, she described memory as both centripetal and centrifugal, drawing us inward to identity while also pushing us outward into the world. It is, she said, “like an umbilical cord,” a connection between self, place, history, and earth. That connection has given back to her in profound ways: uncovering her family’s past in Brest, reclaiming a Jewish identity strong enough to carry her to the mikvah, and embracing the role of the candle child: the one who keeps memory alive for the next generation.

- Memory Embrace memorial opened on 28th July 2025 Photo credit: The Together Plan

- Kathy speaking at the reception after the opening of ‘Memory Embrace’ Photo with permission of Kathy Balgley

- Kathy and Nina at the Bronna Gora killing fields, 29th August Photo with permission of Kathy Balgley

- Kathy at Bronna Gora memorial Photo with permission of Kathy Balgley)

- Kathy with the delegation in Brest the day after the memorial opening Photo with permission of Kathy Balgley

Kathleen’s book, Letters to My Father, grew from that process of self-discovery, but it also became something more: a gift to others, a way for stories nearly lost, to spark recognition across time and borders. I know this because I am one of those readers, receiving her book in Israel during wartime, and finding myself resonating with her journey as I seek to understand my own. The fact that our stories, across time and continents, echo each other feels like bashert as well.

To stand at the Brest memorial was profoundly moving for Kathleen, but the work does not end there. Memory Embrace will stand as an invitation for others to pause, inquire, and connect. Kathleen’s path and the Together Plan’s mission now intertwine: she has gained deeper insight into her own identity, and by sharing her story, we hope to inspire others to trace their own.

Memory Embrace is not only for those who came before. It is for those of us still searching. It is proof that even when stones are broken, even when stories are nearly lost, memory can be pieced back together. And when we step into the circle, we find ourselves together. F