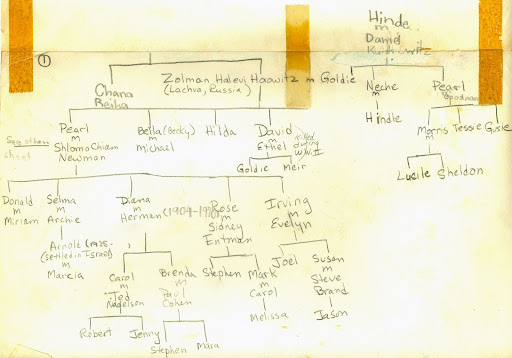

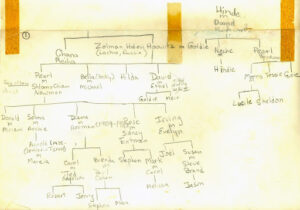

Stephen’s original hand-drawn tree from his 2nd-grade family report assignment.

By Tasha Ackerman

Most people cannot attribute the origins of their lifelong hobby to a 2nd grade class project, but for Stephen Cohen of New York, his family tree which now includes thousands of people began with a hand-drawn assignment from when he was just seven years old.

As Stephen’s tree grew from his family in New York, Stephen discovered that his family roots were entirely from the Pale of Settlement, the regions in Western Russia where, under the Russian Empire, Jewish people were given legal authorisation to reside from the late 18th to early 20th century. This area included parts of present-day Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Moldova, and Belarus, many of which Stephen has been able to trace his ancestry to. This system officially established under Catherine the Great was designed to restrict their opportunities in terms of occupations, education, political representation, and residency requirements for the Jewish people, yet also granted them autonomy for cultural development and religious freedom.

It’s one thing to consider this type of existence through a historical lens, but history comes to life when understanding what your relatives experienced. Stephen shared an anecdote: In the Russian Empire in the mid-1800s under Tsar Nicholas I the Statute on Conscription Duty made it compulsory for male Jews to sign up for military service for a 25-year period. Jews were required to provide conscripts between the ages of 12 and 25, whereas for others the conscripts were between 19-35. (read more). If you had two sons, one was required to attend. In the army service, there were many obstacles to maintaining a Jewish lifestyle, the lack of kosher food being just one. In order to avoid the military draft, Stephen’s great-great-grandfather, Avraham, (who came from either Volya or Lenin in Belarus – a conundrum yet to be solved) changed his name from Kaplan to Naimon. Naimon means “new man” in Yiddish, so with this government fake out, he was the new man in town and evaded military service. Naimon became Newman when eventually translated into English. Stories like this show how a name can hold so much more significance than assumed at face value.

When Stephen began this project in 1970, at the height of the Cold War, there were no internet or records accessible to him. The only access he had to learning this history was by speaking with relatives. However, at that point, he was asking questions from his seven-year-old perspective. Questions such as: Where were you born? What year were you born? Etc. One question he didn’t know to ask at the time, that he would ask now if he had the opportunity: Who were you named after?

Stephen’s original hand-drawn tree from his 2nd-grade family report assignment.

It is a tradition amongst Ashkenazi Jews to name children after deceased family members who were admired. As Stephen’s map extended beyond the family members who he knew personally, he found that these naming rituals could help serve as confirmation of the existence of family members across distant lines. For example, he can trace that the name Daniel has continued uninterrupted in his family for 200 years. In the Kantorovich family, Stephen named his son Daniel for his great-grandmother Dina. Dina had been named for her great-grandfather, Daniel, born in 1826, who was called der zeyde Daniel, who was named for his grandfather, also Daniel Kantorvich who lived from 1776-1821.

The Together Plan’s archive services helped find records of the earliest member of the Gurewicz line of Stephen’s family tree, Leyba, who was born sometime in 1746. Stephen has connected with several distant family members through his research. He was once able to converse with a distant cousin living in Israel over the phone in Yiddish. He described the experience as freaky since her intonation and accent were exactly that of his late grandmother. He explained it was almost like having the opportunity to speak to his grandmother again.

In genealogy, the biggest puzzle is known as a brick wall: when you reach a point in your research that seems unanswerable. There can be many causes for brick walls. For example, women were often left out of public records. For men, you can find draft records, property ownership, and surnames remain consistent. Nicknames are another example, there is no way to find records of someone based on their nickname.

Through his years of research, Stephen has gained skills and strategies to tackle these brick walls. On top of the Hebrew script he was taught growing up, Stephen learned to read Russian characters, so even without a deeper understanding of the language, he can independently search for records of his ancestors. He has learned the right questions to ask and to look in diverse places for information. Even if a physical record may not be available, one’s location can be proven by cross-referencing the stories he’s been told with newspaper archives of local events. Through connecting with relatives and gathering stories he was also able to identify and verify nicknames that were used by some family members – a real piece of detective work!

“It’s not just the names and dates of people, but stories.” Throughout Stephen’s research, which spans multiple countries, getting records from Belarus has been a major brick wall. There are many stories he’s been told by relatives that he would love to confirm. For example, his maternal great-grandmother, Perl Gurewicz, supposedly almost drowned when there was a flood from the Pripyat River. From research, he can tell that it was a marshy and swampy area. Since he knows that she was born in 1883, finding evidence of this flood in the late 1880s or early 1890s could confirm this story. “These questions give local colour to genealogy… colour surrounding people themselves” Stephen would love to ask more questions, seeking answers that could confirm these stories. However, the archives are not accessible online making it impossible for him to continue his research independently.

Stephen shares how an interesting photo can lead to a cross-continental story. He shares a photo of his great aunt Beyle Gurewicz Nayman standing next to a print of a smaller photo of her husband, Mikhl Nayman. The photo was presumably taken while he was away at war. By connecting photos, stories, and archival records, Stephen can now narrate this family’s journey. See, while Mihkl was serving in the army, he was captured and held as a prisoner of war by the Japanese during the Russo-Japanese War from 1904-1905. Shockingly, Mihkl was treated far better under Japanese captivity than he had been as a Tsarist soldier. Once he had returned home, to the region that is now modern-day Belarus, he heard the warnings of what was coming for the Jews. That threat combined with his new knowledge that life for Jews could be better outside of the Russian Empire, he decided to leave for America.

Read the full story here.

I asked Stephen what the significance of this project was – why spend so much time and effort chasing these stories? His response surprised me. He explained that his background is in chemistry, so as a scientist, he looks at his genealogy project as “the opposite of entropy.” Entropy is the accumulation of disorder in the universe. Through genealogy, he can put some order back into the universe through the recollection of information. It is restoring order for him and his family members. It brings order back into the family and creates an opportunity for relationships that may have been severed generations ago to be recovered. “It brings order, it brings connection back to my family, and it brings historical sense.”

To my mind – this is what I would call a real ‘together plan’.